The Emperor Trajan

Trajan, Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, has generally been remembered as a ‘good’ emperor. He undertook practical building projects and gave aid to poorer Romans, particularly children. A gifted general, he was close to his soldiers and led them on a number of campaigns which substantially expanded the Roman empire. Two of these campaigns, the first and second Dacian wars, are commemorated on Trajan’s column. It was, in its time, a unique monument, consisting of a 100 foot tall marble column set atop a massive rectangular base and topped by a gilded statue of the emperor himself. Columnar monuments, albeit smaller in scale, were not new to the Romans; there were three things, however, which made this monument unique: the chamber carved in its base to house Trajan’s ashes, the spiral staircase which wound upwards within its otherwise solid marble shaft to a viewing platform at its top, and, most of all, the continuous sculpted frieze which decorates the exterior of the column.

Experiencing Trajan’s Column

Trajan’s column was but one component of the Forum of Trajan, a massive new complex incorporating a huge basilica, market, and libraries– the last, largest, and certainly most impressive of the imperial fora in Rome. The column itself was set in a relatively small court at the north-west end of the forum, beside the Basilica Ulpia and flanked by two libraries, one for Greek and the other for Latin texts. It was once thought that the fourth side of this court, opposite the Basilica, was occupied by a temple to the deified Trajan, but recent excavation appears to show that no such temple existed. This area may have been filled by a portico or a monumental entrance providing access to the column and its surrounding buildings. (For more on the Forum of Trajan, visit the Getty Museum’s ArtsEdNet website).

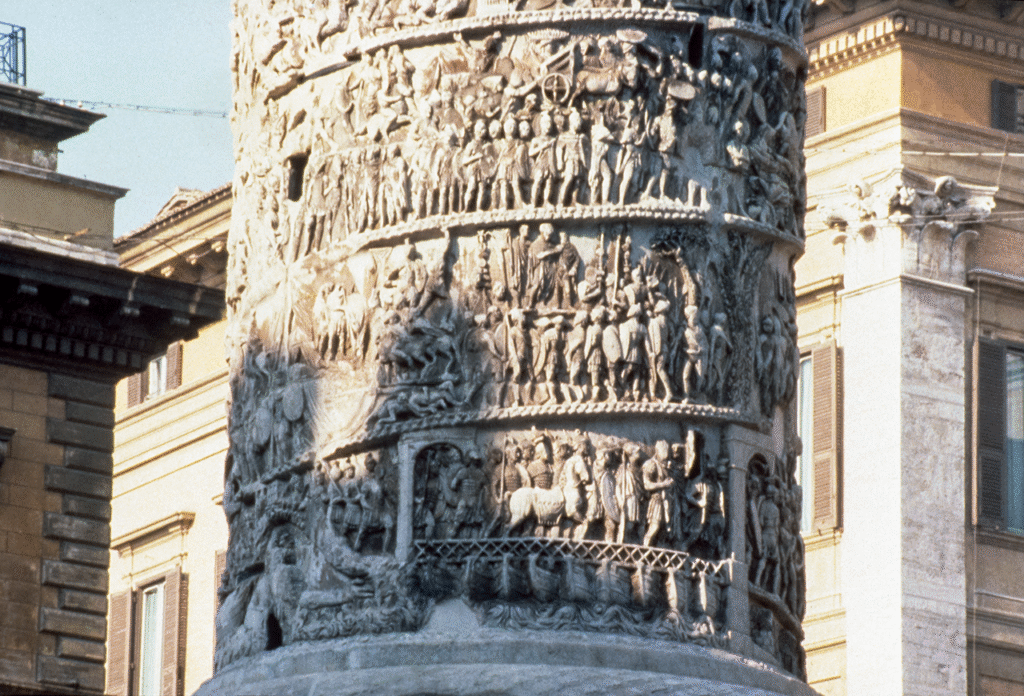

The first thing a visitor to the Column of Trajan would see would be the base, covered with detailed carvings representing spoils of war captured from the Dacians. The carvings which cover the Column itself, though easily accessible to us today through photographs and casts, would have been very difficult, if not impossible, for an ancient Roman spectator to appreciate in full. From ground level, only the lowest spirals are visible in detail. To make matters more difficult, the small size of the court in which the column was placed would not have allowed people to step very far back from the monument, increasing the difficulty of viewing the upper spirals. It has been proposed that the roofs of the two flanking libraries could have been used as viewing platforms (the height of these may have been about equivalent to the current street level from which visitors now peer at the column). Even if this was the case, however, it would have only allowed the spectator to view a few more spirals and it would have been impossible to follow the circular narrative of the relief.

However, it must be remembered that the relief is not all that there is to the Column of Trajan. The sculpture, while doubtless as impressive to the ancient viewer as to the modern one, was not the only ‘interface’ through which a visitor was meant to experience the column. The second crucial aspect of the Column of Trajan, and one which is unfortunately seldom experienced by modern visitors, is the combination of spiral stairway and viewing platform. Even to a modern visitor, accustomed to office towers and glass elevators, the experience of climbing the column’s stairs and viewing Rome from 120 feet in the air is quite impressive; for the ancient Roman, living before the age of the skyscraper and also at a time when the Forum of Trajan was intact, the effect would doubtless have been even greater.

The staircase itself is carved and finished so precisely that one could think it a modern addition. The spiral of the stairs itself serves to thoroughly disorient an ascending visitor. The windows, one every quarter turn, were the only source of light and are placed at such a height that it is impossible to see anything but sky. The whole experience of climbing the column, then, involves a long, twisting ascent, punctuated by bright rectangles of light and culminating finally in a sudden ‘epiphany’ as the climber emerges into the bright light of day on the viewing platform. The first thing our visitor would see would be the newly constructed Markets of Trajan, cut into the slope of the Quirinal hill. Turning to the right, our visitor would be able to gaze along the length of Trajan’s Forum all the way down to the Colosseum. (view from top) This view would have been dominated by the massive roof of the Basilica Ulpia, with its gilded bronze tiles blazing in the sun. Another quarter turn would face the visitor to the Capitol, and a further turn to complete the circuit would provide a view out over the Campus Martius.

How might the impact of such an experience have compared with standing on the ground, craning one’s neck while squinting at the spiral relief carvings? (View from bottom) Conceivably, the ascent and resulting view may have been thought of by the column’s designers as a more important device for experiencing the column than the carvings themselves.

Carving Trajan’s Column

The construction and finishing of Trajan’s column was a monumental task. At Luna (near Cararra in northern Italy) workers quarried the components of the column: eight solid marble blocks for the base, twenty massive marble drums measuring three and a half meters in diameter for the column shaft and capital. These were shipped down the coast and up the River Tiber, and then dragged to the construction site near the Capitol. Once the base had been assembled, work on the column drums could begin. Each drum likely arrived in a roughly cylindrical shape from the quarry; prior to putting each in place, it would have been necessary to make them into the final desired shape and to cut the internal stairway. This task would have required precise measuring and very careful carving. As each drum was lifted into place, it was secured to the one below by metal dowels fitted into the upper and lower faces of the drums and secured with lead. The lead was poured in via a channel cut into the upper face of the lower drum; it was these channels which medieval scavengers used to guide them to the metal dowels, leaving large pits hacked into the surface of the Column at various places along the drum joins.

When was the spiral relief itself carved?{1} This question has been much debated, but evidence from the reliefs themselves seems to indicate that the column drums were carved after they had been put in place, and perhaps carving actually began before all the drums had been raised. The carving appears to have started from the bottom and proceeded left to right up the shaft in a spiral. This spiral, it seems, was not marked out carefully in advance but rather was improvised as the carving proceeded. The top border of the spiral was generally not defined as the frieze was carved, but was left to be formed by the ground line of the spiral as it wrapped around and up the column. Often, objects from the lower spiral can be seen jutting into the groundline of the spiral above, which is often dramatically adjusted to avoid interfering with the scene below.

Sometimes it seems that the carving of the reliefs got ahead of the carving and assembly of the drums. This is indicated by cases where the upper border of a spiral follows along the upper edge of a drum, while the lower border continues to rise. The construction site must have been a scene of hectic activity.

The height of the spiral varies greatly, from about 0.8 m to slightly over 1.5 m. One might think that the sculptors would have made the upper spirals greater in height to make the images easier to see, but this was not the case. In fact, the spiral maintains approximately the same width (1.1-1.2m) between the 1st and the 13th turn, then gets narrower as it proceeds up the column, shrinking to its narrowest at the 19th spiral, and then only on the last two drums widens to its greatest size. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the sculptors were not sure just how much space they were going to have to fit in all their scenes. This makes even more sense if the column was assembled while the sculpture was in progress: only when the final drums were placed on top of the column were the sculptors finally sure of how much space they had. Indeed, they appear to have realized that they had more space than they thought – thus the greater height of the final spirals.

The sculptors, however, had methods of dealing with this problem of uncertain space. Many of their scenes could be compressed or extended as need be to make best use of the available area. A good example is the adlocutio scene, which consists generally of Trajan on a podium flanked by his officers and addressing the troops assembled below. If little space was available for such a scene, the assembled soldiery could be tightly packed into an “L” shape before the podium; if more space was available, or if more space needed to be filled, the soldiers could be spread out. Details such as this, taken into consideration with the varying height of the spiral, make it clear that the sculptors did not have the benefit of a detailed mockup or cartoon to guide them in their work.

Tools and Techniques

How did the carvers and sculptors actually execute their work? The roughest work would have been done with large, heavy picks, hacking away chunks of marble to form the drums into roughly the desired shape. Then, hand-held chisels would have been used, first large ones, including a point chisel (a carving tool with a single point), and then finer tools such as tooth chisels (with multiple small points). In some cases, particularly at edges and angles, a flat chisel (with a sharp straight blade at its end) was used to bring the stone to a fine, accurate finish. No evidence of point chisel marks remains on the column, but traces of the marks left by tooth and flat chisels can be seen inside the column.

The exterior of the column is even more finely finished. There are no traces of either the point or tooth chisel left anywhere on the sculpted frieze, although we know from examples of unfinished Roman carvings that these tools were used to rough out the carved images. Instead, the surface shows the marks of even finer tools, mainly flat and round-headed chisels, scrapers (a fine-toothed tool used to scrape away stone), and rasps. It seems that these tools were essentially the same as the hand tools still used by modern sculptors (modern tools). Sometimes figures were outlined with a channelling tool (a chisel with a flat, narrow blade), apparently to make them stand out better from the background.

No part of the frieze was ever brought to a polished finish, but every preserved portion of the original surface shows some sort of tool mark. The years have taken their toll on the surface of the column’s carvings. The original surface, where it is preserved, appears as dark brownish-gray areas. In these areas, the detail is sharp and tool marks are preserved. Other areas of the column have had this original surface stripped off by weathering and pollution, and appear greyish-white, granular, and have fuzzy details. The difference between these two types of surface is very clear on the stone. (See View of contrasting surfaces).

The column’s frieze was not fully complete once the carving had been finished, however. Provisions were made in many places for metal attachments to be added, mainly tools and weapons held by soldiers, and small holes were drilled into many hands for these miniature implements to be inserted. It seems, however, that this process was rather haphazardly executed. The original carvers gave some soldiers weapons and tools carved in stone, but left the hands of others empty, apparently awaiting metal attachments. In the end, however, not all of these hands were filled and many of the column’s figures were left working or fighting with invisible weapons. Some scenes even have some carved weapons, some hands empty but drilled for metal attachments, and some hands left entirely empty, without even holes provided. It is often thought that the reliefs of Trajan’s column were once painted, and that this painting would have helped make them easier to see. However, there appears to be no trace of any paint anywhere on the column, and it may also be doubted whether the addition of bright paint to such small, detailed reliefs would have made them any easier to make out. Some Further Reading on Trajan’s Column and its Sculpture: C. Cichorius, Die Reliefs der Trajanssäule, Berlin 1896, 1900. [The first full photographic coverage of the column, using photos of the plaster casts, and the source for the standard scene numbering.] F. Lepper and S. Frere, Trajan’s Column, Gloucester 1988. [A reprint of Cichorius’ photos with an extensive commentary in English.] S. Settis, A. La Regina, G. Agostie, and V. Farinella, La Colonna Traiana, Rome 1988. [Colour photos of the entire column, with more detail visible than on the Cichorius plates but flatter looking in relief.] P.M. Monti, La Colonna Traiana, Rome 1980. [A short work but with some good detail shots and a useful (if sometimes inaccurate) set of line drawings.] P. Rockwell, “Preliminary Study of the Carving Techniques on the Column of Trajan,” pp. 101-111 in Marmi Antichi (Studi Miscellanei 26, 1985). Ibid., The Art of Stoneworking: a Reference Guide, Cambridge 1993.

FOOTNOTES

{1} For the following, I am greatly indebted to Peter Rockwell for many discussions on the various theories and for much clarification on (and some firsthand experience of) the practicalities of marble carving